[1]

[1]

If you’ve ever been held up at gunpoint, you know that your life doesn’t flicker before your eyes in some dreamscape manner. No. You are unfalteringly present. Mind and body tightly wound as one. The surge of fear running through your veins is so great that makes it impossible for you to escape your flesh. Even though you’ve told yourself before that you’d be ready to let go, that you have no regrets, you’ve been the best person you could’ve possibly been—even though you’ve told yourself this a dozen times over, the current of electricity in your body tells you to remain. And if you so happen to pass this moment without harm, it is not a sigh of relief you breathe, no thanks you give. Instead, you feel a hot dusty dry anger rise. An anger that your freedom to life—if that is any sort of freedom at all—can be totally and completely compromised by the choices of one individual. It’s precisely this anger that festers throughout the earth as progress continues—

progress that is defined by mankind’s ability to create and end lives at any given time.

FAIR CHASE

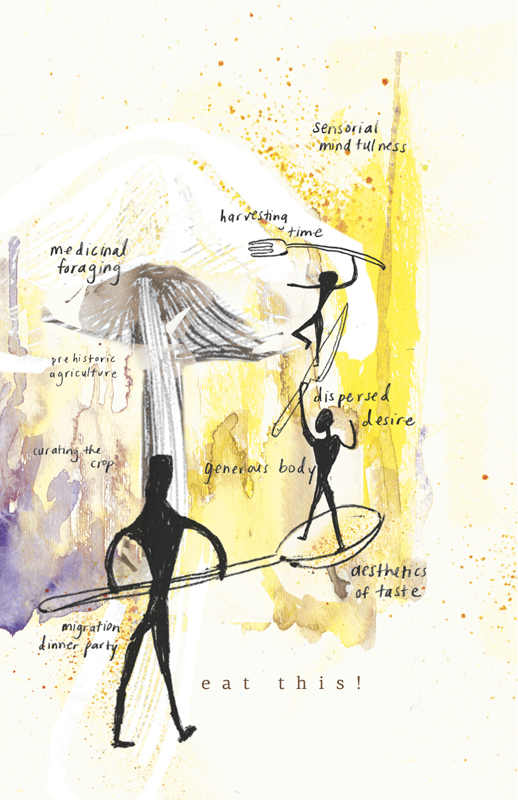

Over 3.4 million years ago, our early human ancestors implemented stones as the first tools for butchering and carving meat off of scavenged carcasses.

[2] It took another million years before these stones were developed into instruments for the actual hunt and pursuit of live animals.

[3] Hunting remained a crucial means of sustenance in the long trajectory of hominids for over two million years. And thus, it is only in recent history, with the onset and proliferation of agriculture by modern humans, that the activity of hunting has come to exist primarily as an activity of leisure or sport.

Artemis with a doe, called the “Diana of Versailles

Artemis with a doe, called the “Diana of Versailles.” Anonymous. 1st-2nd century AD, Roman Imperial copy, Collection of Louvre Museum, Paris, France. [Photograph by Eric Gaba (Wikimedia Commons User: Sting), July 2005.]

Diana of Versailles is the Roman reproduction of the lost Greek sculpture

Artemis with a doe (4th century BC). Flanked by a young sprinting buck, Diana prepares for a hunt, drawing an arrow with one hand, holding her bow ready in the other (only a fragment of the bow remains in its current condition). The sculpture represents Diana’s role as both the goddess of the hunt and protector of the wild.

“The tops of the high mountains tremble and the tangled wood echoes awesomely with the outcry of beasts: earth quakes and the sea also where fishes shoal. But the goddess with a bold heart turns every way destroying the race of wild beasts...”

[4]

Such a formidable huntress would seem to make Diana an unlikely candidate as a protector of the wild, but it’s perhaps out of fear that the animals seek to her for protection. The duality of hunting and protecting nature is not uncommon amongst hunters-cum-conservationists. It’s a position that is embodied at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (the Museum of Hunting and Nature). Located in Paris, the museum is dedicated to the humanist expressions of nature throughout time, vis-à-vis the hunt. The collection houses decorative and fine art objects that depict the hunt, weapons and accessories used in the pursuit, and animal trophies, taxidermies and other relics. The expansive collection bombards us with death in every gallery, reminding us of our historically violent relationship with other animals. For it’s this relationship that is depicted in even the earliest forms of art.

Hunting trophies placed above glass vitrines containing rifles and other weaponry in the Gallery of Trophies.

Hunting trophies placed above glass vitrines containing rifles and other weaponry in the Gallery of Trophies. Vivian Sming. Instagram photograph, May 2011, Museum of Hunting and Nature, Paris, France.

The other aspect of the museum is in its conservation efforts, by way of educating the public and cultivating an appreciation and respect for nature. In the United States, hunting ironically provides the capital for conservation efforts, through the sales of licenses and collection of fees. Hunters can stake claim to their conservationist identities, insisting that the activity of hunting has less to do with the actual

killing of an animal, and more to do with the immersive experience of nature, coupled with the thrill of the sport. Furthermore, to truly learn about a particular species (enough to end its life), hunters must be knowledgeable about its habitat, diet, biological senses, and physical abilities. Through their encounters and gained knowledge, these hunters often hold a deep appreciation and respect for the animals they hunt and kill. After all, love and murder are seldom found to be mutually exclusive.

The question amongst hunters therefore is not whether killing or threatening another living (nonhuman) being is morally wrong, but it is within the specific and nuanced

intentions and

manners in which one kills or threatens. These

intentions and

manners seem to lie somewhere between the spheres of ethics and aesthetics. The

intentions are the

purposes for which one hunts, and can include: hunting for food, for sport, for profit, for population control, and so on. The

manners are

how one hunts, and can include: hunting with or without the use of baits, traps, or dogs, during which particular seasons, the weapons one uses, the distance one maintains—the list goes on. Further concerns include

what one hunts: which particular animals, of which particular sex, or at what particular level of maturity. Each hunt maintains its own specificities, and differs in the nuanced code in which a hunter will allow himself to kill or threaten another living (nonhuman) being.

Fair chase is one of these codes, providing a framework in which hunters can work from. In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt formed the Boone and Crockett Club, which has now become the oldest wildlife conservation in North America. Roosevelt famously earned his nickname “Teddy” precisely for being a proponent of

fair chase. Although he certainly hunted and successfully killed many bears throughout his life, Roosevelt refused to shoot a bear that his assistants had tied up to a tree, on the cause of

fair chase. “

Fair chase, as defined by the Boone and Crockett Club, is the ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit and taking of free-ranging wild, native North American big game animal in a manner that does not give the hunter an improper advantage over such animals.”

[5] Free-ranging animals and

improper advantagemeans that a case such as internet-hunting, in which rifles controlled remotely through the internet were used to shoot and kill animals kept in a confined area

[6], is

not considered

fair chase. Other

improper advantages that are perhaps less clear-cut are still up for debate and vary in legality from state to state.

Diana.

Diana. Augustus Saint-Gaudens. 1892-93, Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA. Gift of the New York Life Insurance Company, 1932.

In the late 19th century rendition of Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the goddess of the hunt balances on one leg, on the tips of her toes, with her bow in full draw. As a sculpture, she is firm and elegant, with target in sight. She has only one arrow, one chance, but the confidence of her stance suggests that she will no doubt make her mark. As a living and naked

[7] (human) body, Diana struggles to maintain pose. The muscles in her leg shake in the effort to remain balanced, and the tension of the bowstring is too great for her arms to sustain. It is within this moment of full draw—prior to the arrow’s release—where she is held forever, where ethics is contained.

LIKE A DEER CAUGHT IN HEADLIGHTS

A deer remains frozen in the middle of the road. Her eyes are designed to allow more light to reach her during the night, and thus, the sudden impact of light blinds her. She remains frozen, her future to be determined by the actions of the entities around her.

[9]

[9]

When faced with the vulnerability and nakedness of another, you are tempted with murder, as you recognize the precariousness of that life in relation with yours.

[8] The face, in screaming, “thou shall not kill” reminds you that yes, you hold a power and responsibility towards my future well-being.

But whatever you do, do not kill me. This scream is not heard through words, but through the presence in our very being. For Emmanuel Lévinas, this concept of

the faceis what successfully prevents us from constantly committing murder on a daily basis, suggesting that presence alone is enough to combat one’s ability and desires to annihilate at any given time.

CATCH & RELEASE [10]

June 28, 2007

Some say our life is insane,

but it isn’t insane on paper.[11]

It isn’t insane on paper.

It isn’t insane on paper.

July 2, 2007

It was an otherwise ordinary day. We were driving—Dad behind the wheel, Mom in the passenger, me in the back. We were driving home, driving somewhere—just driving. A police car started following us (an unmarked car with one blue light on top of its hood). As it approached, the sirens went off and the blue light flashed. We were being pulled over. My dad seemed to ignore this completely, and kept on driving. My mom and I were anxious, and started screaming, “What are you doing? Stop the car!” But my dad didn’t get it. He didn’t understand why he would need to stop. He’s not doing anything wrong, he said. We argued. Dad, this is the

law. I don’t know what’s going on, but you have to pull over unless you want to start some sort of pursuit. And how is that supposed to end? Okay, okay, he pulled over. As the policeman walked towards our car, several other vehicles swarmed around us. It soon became clear that he was not police at all. Dressed in ordinary clothes, the man pointed a gun at my dad and yelled, “Get out of the car!” Other armed men surrounded our car shouting, “Put your hands on your head!” My dad complied, and was promptly handcuffed and escorted to a white van. We were being taken as hostages. My mom told me to call someone—she was next to go. I tried texting [my friend] Iris, but could only form autocorrected gibberish (I had just gotten the iPhone a few days ago

[12]). My phone dropped, and as I reached for it, the back door opened. I was pulled out of the car and dragged towards the van, gun held against my head.

In the van:

an old couple

a teenage girl, all dressed up (on her way to prom perhaps)

my dad

my mom

myself, up next.

Everyone was blank.

Their faces were naked.

Nothing filled my head.

The man pulled down his gun.

“Just kidding!” He smirked.

What?

A camera crew appeared, and the cameras were rolling.

In my frozen state, I recalled footage I had once seen online of a few celebrities, hand-tied and blindfolded, forced to do a number of logic-related tasks. Puzzles.

The website was run by

this man, a man with a vision, and it was his manifesto. I suddenly felt nauseous with the realization that we were being filmed this whole time, and streamed live onto his forum. Millions of viewers watching online, reveling in our live performance of fear.

The man spoke directly into the camera, to his virtual audience:

“Let this be a reminder of what the world can truly be. We need to train ourselves to expect the unexpected so that we can protect ourselves in the future. There is a whole lot of evil in this world, beyond the United States of America—horrors that we haven’t even seen. We need to break out of our sheltered lives and start preparing ourselves for the worst to happen. Now, these folks were extremely lucky that this was just a test. If any situation like this ever occurs again, they will be more prepared to take action. We must remind ourselves that every minute can be our last. We never fully understand the true value of something until it becomes a memory. Let’s not let that happen.”

He spewed on and on, cameras still rolling, but I couldn’t hear anything anymore, or refused to.

“This is an event that I will always remember,” my dad sighed.

We were free to go.

Cameras still rolling.

Anger rising.

LIKE A FISH OUT OF WATER

The greatest symptom of the prey is that the prey is seldom, if ever, involved in discussion of ethics or ethics-making. The predator and the prey hold two distinct sets of ethics. By the very definition of being a predator, it necessitates that the predator’s set of ethics infringes upon the prey’s. These ethics can be formed around the prey, which can call for the prey’s destruction or well-being, but their formation is made largely in absence of any dialogue with the prey itself. (The prey is not necessarily consulted, per se.) Thus, the prey is always subjected to the predator’s ethics and actions, regardless of the ethics the prey may possess. This is not to suggest that the prey holds no power, but the power of the prey is primarily located in its face

[13], its presence, in its very being in the world, and not through a discursive space. Here, I claim the prey as a position, which can be constituted by any number of entities, both living and nonliving, whose ethics and way of being go unheard, and are infringed upon by the actions and ethics of another. In truth, by our very being in this world, we are always making ourselves available as prey, and through our actions, we become predators, subjecting those around us to our own individual set of ethics.

In

Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma (1997), Peter Levine suggests that nonhuman animals are more prepared than humans to face threats at any given time, through their biological responses. Upon threat, animals will often go into an immobile frozen state, if neither options of fighting or fleeing are available. This immobility, however, still contains a significant amount of energy. Levine provides the example of an impala that is caught between a cheetah’s teeth: “From the outside, it looks motionless and appears to be dead, but inside, its nervous system is still supercharged at seventy miles an hour. Though it has come to a head stop, what is now taking place in the impala’s body is similar to what occurs in your car if you floor the accelerator and stomp on the brake simultaneously. The difference between the inner racing of the nervous system (engine) and the outer immobility (brake) of the body creates a forceful turbulence inside the body similar to a tornado.”

[14] Levine further claims that in this frozen state, no pain is experience, as the body provides a natural anesthesia in preparation for death. However, if given the opportunity to flee, the animal is able to charge at a blazing speed, thus releasing all energy held within its frozen state. This biological response is what, Levine argues, allows animals to recover from ongoing threats that would otherwise generate trauma within humans.

Once released back into the wild, we make ourselves available to be caught again. For “a good game fish is too valuable to be caught once.”

[15] Here in the wild we remain, forever negotiating our positions as predator and prey.

- - - - - - - - - -

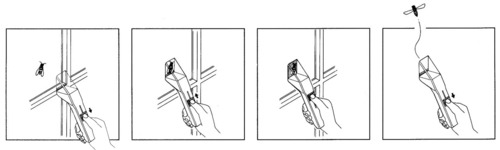

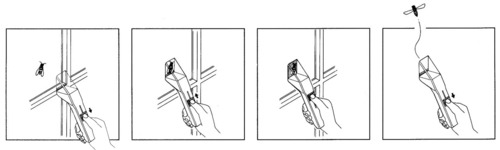

[1] Instructional diagram for “Humane Bug Catcher” by German company Snapy, from PETA’s online store catalog.

[2] California Academy of Sciences. “Oldest evidence of stone tool use and meat-eating among human ancestors discovered: Lucy’s species butchered meat.” ScienceDaily, 11 August 2010.

[3] Lewis, Tonya B. “Baylor University Researcher Finds Earliest Archaeological Evidence of Human Ancestors Hunting and Scavenging.” Baylor University Media Communications, 9 May 2013.

[4] Anonymous. “The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White.” Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

[5] “About the B & C Club” Boone and Crockett Club, 2012.

[6] Schoby, Mike. “Remote-Control Hunting.” Outdoor Life, 2007.

[7] Diana was originally created with a drapery to cover her, which was designed to catch the wind. [Sewell, Darrel.Philadelphia Museum of Art: Handbook of the Collections. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1995. 293.]

[8] These ideas are taken loosely from Emmanuel Lévinas’ concept of the face. [Lévinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 1969.]

[9] Stills from “ABC World News Now: Deer Caught In the Headlights, Literally!” ABC News, 17 November 2011.

[10] This section contains two edited entries from the author’s 2007 journal. The contents of the July 2, 2007 entry recounts the author’s non-fictitious experience during an REM cycle.

[11] Emily Haines & the Soft Skeleton. Nothing & Nowhere. Last Gang Records, 2006.

[12] June 29, 2007 was the release date of the first iPhone.

[13] In reference to Emmanuel Lévinas’ concept of the face. [Lévinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 1969.]

[14] Levine, Peter A. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity to Transform Overwhelming Experiences. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic, 1997.

[15] Mantra of Lee Wulff, proponent of catch and release fishing.

[1]

[1]